A big international success, the HBO series “True Detective” seems to do away with the detective story genre.

You know exactly what it is going to happen but when it happens it still surprises you. So, where is the true of “True Detective”?

Why is True Detective so true?

The question comes to my mind as I watch this powerful series, which tells a noir story unfolding in the deep south of the United States.

No doubt it’s a detective story. A serial killer commits a series of murders in Lousiana. A couple of detectives follow the track for more than fifteen years and, at the end, after a bloody fight they succeed in defeating the evil killer.

So nothing new under sun of the detective stories. Even the main characters correspond to a sort of prototype of detective. Rust (McConaughey) is a cynical philosopher with a sad and dark past to hide; Marty (Harrelson) is a middle-class province policeman that doesn’t want any trouble. He has a present situation to hide (nothing more than a young lover).

Serial killers of course kill young women. And of course there are a lot of clues that point to other suspects, while nobody thus far has ever had a chance to think about who could be the real killer.

What else? Ghettos, preachers, old dollies collectors, fights and misunderstandings, betrayals and all the stuff that makes a detective story a “dark detective story”.

So why is this series so strong, compelling and beautiful? And why is it “true”?

For sure is not a matter of good cinematography (it is something we expect from a HBO series). It’s probably not even a matter of good script or good acting (they are both great and a lot over the average standard).

Probably, I would say, it is a good and well balanced mix of both of these elements. The protagonists act great. Harrelson and McCounaghey are intriguing and ambiguous; all the other actors perfectly embody unfair characters in an unfair place. Everybody and every place transmit a deep sense of discomfort. As a spectator you feel uneasy in watching the scenes and in listening to very well written unusual dialogues. You have the clear feeling that there’s always something going on behind the self-evident surface that is shown: behind the said there is a more profound unsaid, behind what we see there’s a lot more that we just perceive but we are not allowed to see.

But once again this is what we expect from every good detective story. There no need to quote Chandler or Ellroy, everyone among us has his/her own beloved detective novel in his/her drawer.

“True detective” is supposed to be an antologycal series. That means the number 2, 3 etc. will have different characters, different stories and locations and even different directors (but the same script writer, Pizzolatto). It’s a non-common concept for such a successful tv movie. Normally we fall in love with characters and locations, and we are led by our infatuation into following them until the end. The very concept of series finds one of its pillar in the desire of knowing deeper and deeper our heroes (or anti-heroes). In this particular case, however, Pizzolatto has decided to cut off our expectations. We know from the beginning that our preferred “true detectives” will change after the end of the last episode of season 1. I think that this is the point. They are “true” because we get into their lives just for a short period of time, knowing we are going to let them go. They do their best to hook us and we accept this game because we feel (we want to feel) a tranche de vie. They are not true, but we want them to be so. If we think back to the ghetto’s fight episode we could easily realize that it is filmed as if it was a TV program such as “real policeman life”. We feel we are watching a real police attack to the ghetto (there are a lot of real-life TV programs about policeman, fire fighters, doctors and so on). The series want us to believe we are not watching a movie but a detective real life. We are there together with Rust and Marty and we will miss them because we have also seen them getting older and losing their detective job.

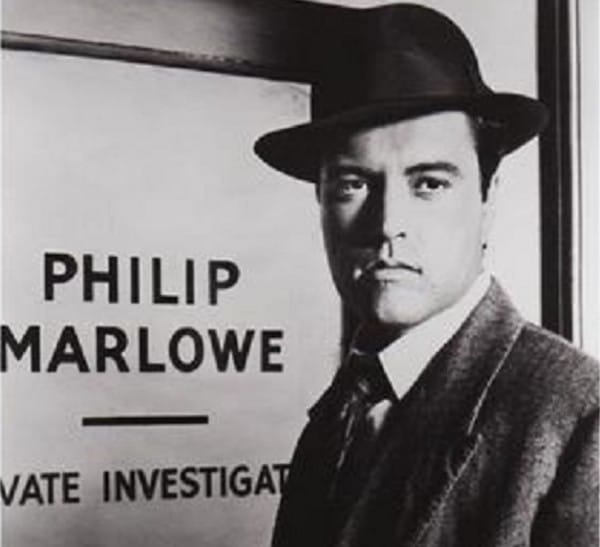

The flash back (flash forward) structure of the series helps the viewer to get more into real detective life. Marlowe never becomes old and fat, Rust and Marty do. So we are watching a series (not a film that normally follows other dramatic rules) but we are not watching a series because is just one shot. We are watching detectives but they will not be detectives anymore when they will solve the enigma. These are the reasons why I would say that “True detective” is “true”: because it is classical. Normally we use this word for arts’ works that comes from ancient times and are created by very well-known artists. I’m sure that ‘classical’ fits this case too: in watching it you expect every single scene, every single dialogue, every single turning point. You know exactly what it is going to happen but when it happens it still surprises you. This could happen only when a single representation transports the audience into generalization, it makes you forgetful of the specific case, and it gives you a tangible perception of offering a deeper level of comprehension of human beings.

Is it a definition of classical? Probably.

Acknowledgements

Image credit: cover, Touch of evil (1958), directed by and co-starring Orson Welles.