This brief article analyzes Egyptian checkpoints as central mechanisms of the police state, a legacy of the Mubarak era (1981–2011) and core feature of today’s political economy of coercion and policing in Egypt. The article is a summary of the author’s ongoing broader research on infrastructures and economies of exception, control and authoritarianism in Egypt. Unlike previous research focused on checkpoints in contexts of conflict or state collapse, this broader work examines their role within a fully operational authoritarian regime and modern nation-state. The research draws more broadly on legal documents, ethnographic fieldwork, and semi-structured interviews, it reveals how checkpoints contribute to a routinized state of exception, legitimized through both military and civil legal frameworks. This exception governs mobility, labor relations, and territorial control.

The Strategic Nature of Egyptian Checkpoints

Checkpoints are pervasive in Egypt’s social and political landscape, appearing as fixed or mobile units across the country. They function as spatial nodes of power, filtering, segregating, and disciplining populations – particularly precarious workers and surplus labor. Often described as kama'in ("ambushes"), they operate with unlimited arbitrary power, fostering ambiguity and fear that reinforce public docility. This unpredictability is intentionally "manufactured" to internalize state power.

Expanded during the 1980s and 1990s counterterrorist campaigns, checkpoints originally trace back to 19th-century Ottoman practices of controlling rural mobility. Rather than responding to concrete threats, they operate as mechanisms of order production and compliance, compensating for the state’s structural inability to regulate daily life. They embody a militarized logic adapted for internal control.

Economic and Social Implications: The Politics of Passage

The analysis employs the concept of the “politics of passage”, coined by Peer Schouten: struggles over the terms of crossing checkpoints that reshape both authority and the conditions of trade and mobility. Checkpoints are cost-effective tools for asserting control over people, resources, and space. In weak economies, they facilitate tight oversight over peripheral regions while outsourcing governance.

Under neoliberal hegemony in the Global South, the capitalist imperative of circulation is inverted: controlling mobility becomes politically useful and economically viable to manage surplus populations. Time – central to capitalist value – is devalued. By slowing or immobilizing movement, checkpoints filter and discipline populations deemed superfluous, reinforcing hierarchies of access and exclusion. A police officer, in an interlocution with the author, candidly put it: “They can wait for hours, even days. We can block them on the bridges as long as we want. What matters is ensuring the important people pass, not those worthless ones.”

Territorialization as Political Technology

Checkpoints do not merely demarcate territory – they produce it. They turn fluid zones into rigid grids of access and exclusion. By controlling the economic “use of land,” they reinforce core-periphery inequalities. Territorial logic also extends to identity, filtering populations through class, ethnicity, and regional origin, materializing “everyday cartographies of exclusion.”

Routinized Exception and the Ban-Opticon

The theoretical framework mobilised for this research draws mainly on Foucault’s concepts of disciplinary power and governmentality. In contrast to Agamben’s notion of the state of exception as a suspension of law, Egypt’s checkpoints operate through a routinized exception – the banal normalization of exceptional governance. Constitutional rights exist at the macro level, but on the ground, checkpoints enact ad hoc exemptions – arbitrary delays, unlawful searches – that escape legal accountability.

This logic aligns with Bigo’s (2006) ban-opticon, which extends Foucault’s dispositif to include liberal legal regimes. It profiles “anomalous” subjects and normalizes surveillance. Egyptian checkpoints, often labeled as “borders” or “military zones,” suspend rights under formal legality, enabling body inspections, movement restrictions, and suspicion-based arrests. A system of preemptive marking identifies risky populations using biometric databases, digital profiling, and predictive policing, where scars, tattoos, or clothing can trigger detention. At an Egyptian checkpoint, one might be held for anything from a bounced check to an officer’s intuition.

Egypt’s Legal Paradox and the Police State

Though Egypt formally operated under emergency law for decades, its routinized exception emerges from the interplay between ordinary law and political economy, producing a logic of police governance. The tension between rule of law and police rule is mediated through a permanent state of exception, paradoxically overseen by Egypt’s legal and judicial system. Checkpoints are sites where law and enforcement merge. Exception is not a reaction to crisis, but embedded in institutional routine and everyday practices.

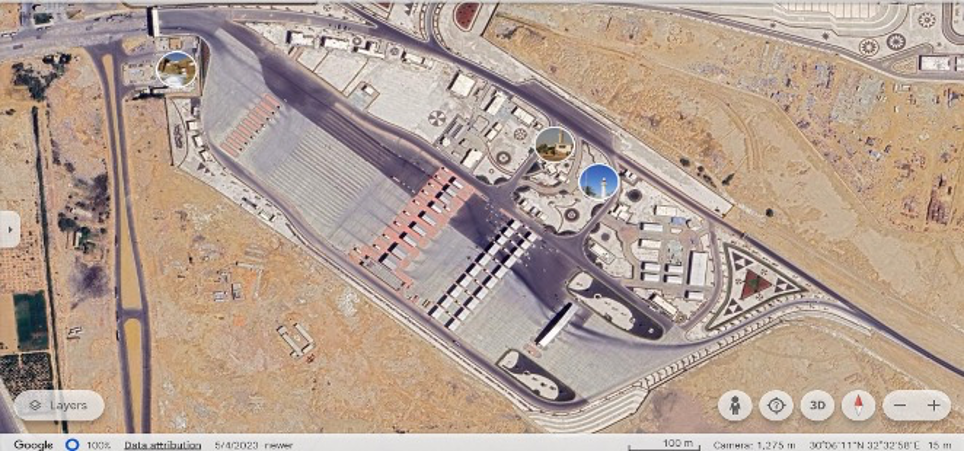

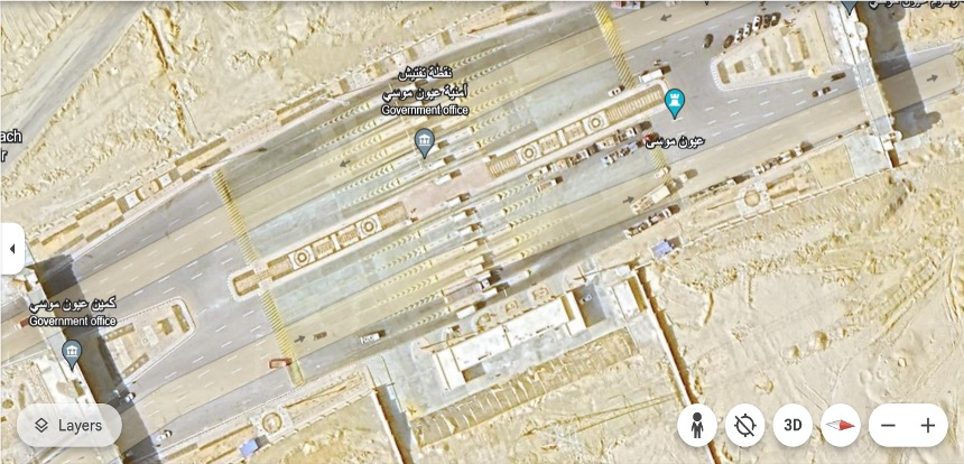

Zoomming in on The Martyr Ahmed Hamdi Tunnel Checkpoint

Located 136 km from Cairo, this checkpoint separates Sinai from mainland Egypt. It holds strategic significance due to the tunnel’s location, the sensitivity of the Suez Canal, and Sinai’s geopolitical position. Legally classified as a border checkpoint – despite international borders being 300 km further east – it redefines internal territory as “border zones,” suspending regular law and enabling a routinized exception.

South Sinai’s economy, driven by foreign tourism, generates seasonal demand for service workers. Yet, it is also a highly restricted zone where checkpoints serve as primary filtering mechanisms. The area is intertwined with informal and illicit economies, including marijuana trafficking, extortion for property protection, and construction material smuggling by Bedouin tribes.

The western checkpoint at the tunnel is complex and multilayered: a bomb-detection gate, technical inspections with dogs, manual vehicle and ID checks by soldiers, and airport-style electronic screening.

Social Impacts and Discipline

Checkpoint experiences vary widely based on class and ethno-political identity. The precarious – young people, the unemployed, informal workers – are most vulnerable to humiliation and delay. Lacking valid contracts or having criminal records, they face harsher inspections and verbal abuse. Leaving an ID at a checkpoint is both a logistic burden and a form of subjection, exposing individuals to further scrutiny.

Moral policing is prominent: women traveling with unrelated men may be harassed; unmarried couples are often humiliated. Legal alcohol possession may lead to confiscation and public shaming.

For those with criminal records, mobility is heavily restricted, job prospects are limited, and surveillance is constant. Former political prisoners are routinely stopped and barred from entering South Sinai. A local saying summarizes this geography of control: “Asphalt for the government, desert for the tribes.” Movement along paved roads is tightly regulated by checkpoints, while just meters away – on beaches or in the mountains – the police disappear, drugs are tolerated, and gender norms are relaxed. These “liberated zones” are tolerated for tourism’s sake.

In response to pervasive control, Egyptians often adopt docility and invisibility to avoid delays. Docility becomes a means to pass faster through checkpoints. The system reinforces a hierarchy where regulation, discipline, and violence prevail over law. In some cases, torture is perceived as a more expedient path to resolution than navigating the legal system. Thus, checkpoints are not only tools of repression, but mechanisms that reproduce political and social order by naturalizing submission and atomizing resistance.

Conclusion

Egyptian checkpoints are more than security measures – they are permanent, routinized instruments of control. They institutionalize a state of exception embedded in daily life, blending civil and military law to create spatial regimes of exclusion. As socio-technical devices of territorialization, they segregate populations, restrict market access, and entrench spatial and class inequalities. Within a neoliberal political economy, they discipline surplus populations and consolidate state authority. By operating as “ambushes,” checkpoints not only enable negotiation and resource extraction, but strategically produce docility, demobilize resistance, and normalize subjugation.

Bibliography

Agamben, Giorgio. 2005. State of Exception. Translated by Kevin Attell. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Bigo, Didier. 2006. Security, Exception, Ban and Surveillance. In Theorizing Surveillance: The Panopticon and Beyond, edited by David Lyon, pp. 46–68. Portland: Willan.

Schmitt, Carl. 2008. Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Schouten, Peer, Max Gallien, Shalaka Thakur, Vanessa Van Den Boogaard, and Florian Weigand. 2024. The Politics of Passage: Roadblocks, Taxation and Control in Conflict. DIIS Working Paper Series: Roadblocks and Revenues (01). Danish Institute for International Studies. ISBN 9788772361505.